Curtis walked through the front door of Snyder’s Pet Shop in Riverside, California.

“Did you come by to window- shop?” the manager asked.

The 11-year-old nodded.

“OK, just make yourself at home!” the man called cheerily. “By the way, I have new animals in the back that you might like to see.”

Curtis headed for the back of the shop. He, his older brother, and his dad had given the shop a lot of business since moving from Compton. The boys had owned king and gopher snakes, common and exotic tropical fish, a crow that stole shingles from the neighbor’s roof, and an opossum that could play dead. They also had a barn owl, a bantam rooster, and a loftful of pigeons.

Curtis had been to the pet shop with his dad so many times that the employees trusted the boy. They gave him complete roaming privileges even when his father wasn’t with him.

Stopping in his tracks, Curtis slowly turned his head and searched the cages in the dimly lit room. His eyes riveted on a pair of brown eyes.

“Oh!” he gasped. “What a cool little monkey!”

Forgetting everything else in the room, the boy cautiously approached the cage of the animal. It looked like a miniature chimpanzee. Eyes sweeping over the animal’s shiny, reddish-brown fur, Curtis thought, I’ll bet he’d learn a bunch of tricks real fast! He looks really smart.

Curtis felt the wallet in his pocket. He had some money he had earned and saved.

But Mom and Dad wouldn’t want a monkey in the house, he thought. Maybe I’ll talk to them about this one.

But then he remembered that his parents always had a good reason for their rules. It would probably be no use trying to change their minds.

“It’s a squirrel monkey,” explained the manager, coming through with a load of empty cartons. “Look how alert his eyes are!”

On a sudden impulse Curtis blurted out, “How much is this monkey?”

“Twenty-five dollars,” answered the manager.

Almost before he knew what he was doing, Curtis had plunked down money from his thick wallet for the monkey, a collar, and a leash.

The manager transferred the monkey to a wooden-slatted crate. Then the man and the boy bent the four wire loops to attach the wire-mesh cover over the nervous monkey.

“Think the driver will let you take this on the bus?” asked the store manager.

“I hope so.” It was his parents–not the bus driver–that Curtis was worried about.

What am I going to do? thought Curtis as he got off the bus and walked toward home. Will Mom and Dad be mad? Will I have to take the monkey back?

Curtis slipped in through the back door. Instead of going to his room, Curtis–with monkey crate in hand–carefully worked his way downstairs. Crossing the basement storeroom, he made his way to a small bathroom no one used and set the crate down in the shower stall.

Great! He’d made it home with his very own monkey, and the hiding place was perfect–his parents would never suspect anything!

Running upstairs, Curtis grabbed an animal bowl and filled it with water. Then he put some pieces of bread and fruit in another bowl. Back down in the shower stall Curtis talked quietly to his new pet before carefully lifting the wire-mesh lid and setting the bowl of water in the crate.

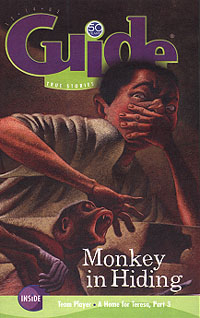

Will the monkey let me pet him? Curtis wondered. But before his hand could reach for the monkey, the monkey leaned toward his hand–and bit it!

“Yeo-o-ow!” hollered Curtis. “What’d you do that for?” Then he clapped his unbitten hand over his mouth, hoping no one had heard him.

“Don’t bite me. I’m your friend,” said Curtis, trying not to feel scared of the monkey glaring up at him through the wire top of the crate.

The monkey waited until Curtis had finished placing the food dish in the crate, and once again pounced and planted a second row of teeth marks beside the first.

“Why, you little–” exclaimed Curtis in a painful whisper while he examined his throbbing wrist.

For the next few days Curtis, his heart heavy with guilt, secretly continued caring for his hidden pet. Soon both arms were covered with scratches, bruises, and teeth imprints.

If the monkey had some exercise, maybe he wouldn’t be so mean, Curtis thought one day. I’ll wait until Mom goes upstairs to fold laundry. Then I’ll sneak him out.

Tugging impatiently on his new leash, the monkey preceded Curtis down a little lane that led to the family’s garage area.

“Hold up!” Curtis ordered. “You need to learn some manners.”

As if understanding what Curtis had said, the monkey abruptly stopped and sat up on his haunches.

“You’re a smart little guy, aren’t you?” chuckled Curtis.

Keeping his alert brown eyes on Curtis, the monkey slowly raised his hands to his neck, then quickly unsnapped the leash from the collar and took off in a sprint down the lane. Curtis chased the monkey at full speed–across a gully, through a barbed-wire fence, into a clump of trees, and through large rock formations. But the monkey continued to outdistance him. Before long the monkey ran out of Curtis’s view–and life–forever.

Exhausted and discouraged, Curtis trudged back up the little lane. His mother was waiting for him on the back porch. The boy could tell from the look on her face that she knew everything.

“I’m sorry, son,” she said.

He hung his head in hurt and shame.

“I saw the whole thing from the upstairs window. Before that, I saw the animal bites on your arms and hands.”

“Mom,” began Curtis, “I’m so sorry I tried to deceive you. It felt horrible, and I deserve to be punished.”

“Son,” said his mother, “the guilt you’ve been carrying, the monkey bites, and losing your pet have been your punishment.”

The next thing he knew, Curtis was in his mother’s arms crying.

“God has a lot of different ways to show us our mistakes,” she said, gently rocking him back and forth. “One of those ways is by allowing us to have what we want–and to let us learn from the natural consequences of having gotten what we wanted. I think this was one of those times.”

“I think so too,” agreed Curtis, suddenly feeling lighter and freer than he’d felt since the day he’d snuck the monkey home.

BY THE WAY . . .

Curtis’s love of animals eventually led him to be a summer camp nature director. For 20 summers he has served as nature center director and director for a number of summer camps. Curtis is now a Seventh-day Adventist teacher who keeps animals in the classroom for his students.

When Curtis finished his two-year apprenticeship to become a Master Falconer (the highest level that federal and state governments recognize as trainers of birds of prey), he was one of only 611 people in the state of California (population 32 million) to hold this distinction.

Reprinted from the May 30, 1998, issue of Guide.

Illustrated by Ralph Butler